Why a European Day of Languages?

Why a European Day of Languages?

There have never been more opportunities to work or study in a different European country – but lack of language competence prevents many people from taking advantage of them.

Globalisation and patterns of business ownership mean that citizens increasingly need foreign language skills to work effectively within their own countries. English alone is no longer enough.

Europe is rich in languages – there are over 200 European languages and many more spoken by citizens whose family origin is from other continents. This is an important resource to be recognised, used and cherished.

Language learning brings benefits to young and old – you are never too old to learn a language and to enjoy the opportunities it opens up. Even if you only know a few words of the language of the country that you visit (for example on holiday), this enables you to make new friends and contacts.

Learning other peoples’ languages is a way of helping us to understand each other better and overcome our cultural differences.

Language skills are a necessity and a right for EVERYONE – that is one of the main messages of the European Day of Languages.

The overall objectives are to raise awareness of:

- Europe’s rich linguistic diversity, which must be preserved and enhanced;

- the need to diversify the range of languages people learn (to include less widely used languages), which results in plurilingualism;

- the need for people to develop some degree of proficiency in two languages or more to be able to play their full part in democratic citizenship in Europe.

… the Committee of Ministers decided to declare a European Day of Languages to be celebrated on 26th September each year. The Committee recommended that the Day be organised in a decentralised and flexible manner according to the wishes and resources of member states, which would thus enable them to better define their own approaches, and that the Council of Europe propose a common theme each year. The Committee of Ministers invites the European Union to join the Council of Europe in this initiative. It is to be hoped that the Day will be celebrated with the co-operation of all relevant partners. Decision of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, Strasbourg (776th meeting – 6 December 2001)

Source: http://edl.ecml.at/Home/WhyaEuropeanDayofLanguages/tabid/1763/language/en-GB/Default.aspx

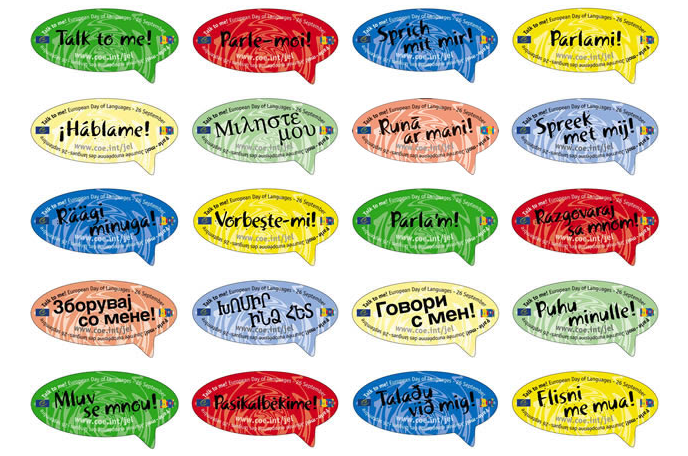

Moving into the polyglot age

If someone said to you ‘flisni me mua’, would you know what it meant, or even which language was being spoken? With some 225 indigenous languages, Europe’s linguistic heritage is rich and diverse; a fact to be celebrated. But how good are Europeans at learning the languages of their near (and not so near) neighbours? Many Europeans may think that a monolingual way of life is the norm. But between a half and two-thirds of the world’s population is bilingual to some degree, and a significant number are ‘plurilingual’, that is, they have some level of competence in a range of languages (understanding, and/or writing, and/or talking, …).

Plurilingualism is much more the normal human condition than monolingualism. There are millions of people who think they know no language other than their mother tongue; however many of them know some level of another language. And yet the opportunities to learn a new language are today greater than ever. To emphasise the value of language learning, the Council of Europe established the European Day of Languages (EDL), which is celebrated each year on 26 September. The idea behind the EDL is to encourage ‘plurilingualism’. This is neither new nor obscure. It is a fact of everyday life among many peoples in Africa and Asia, and is the norm in parts of Europe, particularly Benelux and Scandinavia and also around the Mediterranean. And it doesn’t mean frightening people into thinking they have to aspire to ‘native speaker’ level. The object is to be able to communicate, and be understood, according to your own needs and requirements. The international spread of English seems irresistible, and surveys bear out the impression that acquiring some level of English is a priority for the largest number of language learners (one in three claim they can converse in it, according to Eurobarometer).

Yet, once this has been achieved there is no reason to stop at English. Many other languages are also valuable tools to get the most from life’s experiences, whether for work or just travelling. One of the ironies of a globalised world is that the marginal value of English could decline. As more and more people become proficient in today’s ‘lingua franca’, what will make a difference is the ability to speak additional languages. In the worlds of work and education native English speakers will have to compete with candidates who already have their mother tongue, plus English and, increasingly, a reasonable knowledge of a third or fourth language under their belts. And language ability brings more than just economic benefits. It encourages us to become more open to others, their cultures and attitudes, and also promotes greater mental flexibility by allowing us to operate different systems of representation and a flexibility of perspective. We should not underestimate the value of language learning in giving us insight into the people, culture and traditions of other countries. People who can communicate confidently with those of other cultures are likely to be more tolerant. And remember that to be monolingual is to be dependent on the linguistic competence, and goodwill, of others. Learning to use another language is about more than the acquisition of a useful skill – it reflects an attitude, of respect for the identity and culture of others and tolerance of diversity.

The Council of Europe pioneered a programme to enable people to gauge their level of proficiency in a foreign language. The European Language Portfolio project aims to motivate learners by acknowledging their efforts to extend and diversify their language skills at all levels; and to provide a record of the skills they have acquired which can be consulted, for example, when they are moving to a higher learning level or looking for a job at home or abroad. Based on a grid system language learners can assess their abilities –understanding, reading, speaking, and writing – and grade these according to six European levels. These standards have been adopted by the main certification bodies in Europe, by many member states and by the EU, in particular as part of its Europass scheme, a system designed to make individual abilities more transparent and comparable across member states. One of the central planks of the European Day of Languages is to reinforce the idea of language learning as a lifelong process. Many adults believe that having missed (or even wasted) the opportunity to acquire a new language during their years of formal education, it is too late to restart the process. It isn’t. All over Europe, classes, programmes and techniques (from books to CD-ROMs) are available to improve language abilities. What’s often missing is the personal motivation to overcome the ‘language fear factor’. Many people develop their language skills after leaving school or university. This is not so surprising; language learning in school is often seen as an obligation rather than an opportunity. It is only when we begin to explore the world outside, whether for work or leisure, that we come to learn the value of other languages. And for some words of encouragement, each additional language learned becomes progressively easier. So when you have cleared the first hurdle, and you fancy a stab at Hungarian, or Cantonese, just give it a try.

Source: http://edl.ecml.at/Home/Movingintothepolyglotage/tabid/2970/language/en-GB/Default.aspx

Language facts – Did you know that…

Language facts – Did you know that…

01 There are between 6000 and 7000 languages in the world – spoken by 7 billion people divided into 189 independent states.

02 There are about 225 indigenous languages in Europe – roughly 3% of the world’s total.

03 Most of the world’s languages are spoken in Asia and Africa.

04 At least half of the world’s population are bilingual or plurilingual, i.e. they speak two or more languages.

05 In their daily lives Europeans increasingly come across foreign languages. There is a need to generate a greater interest in languages among European citizens.

06 Many languages have 50,000 words or more, but individual speakers normally know and use only a fraction of the total vocabulary: in everyday conversation people use the same few hundred words.

07 Languages are constantly in contact with each other and affect each other in many ways: English borrowed words and expressions from many other languages in the past, European languages are now borrowing many words from English.

08 In its first year a baby utters a wide range of vocal sounds; at around one year the first understandable words are uttered; at around three years complex sentences are formed; at five years a child possesses several thousand words.

09 The mother tongue is usually the language one knows best and uses most. But there can be “perfect bilinguals” who speak two languages equally well. Normally, however, bilinguals display no perfect balance between their two languages.

10 Bilingualism brings with it many benefits: it makes the learning of additional languages easier, enhances the thinking process and fosters contacts with other people and their cultures.

11 Bilingualism and plurilingualism entail economic advantages, too: jobs are more easily available to those who speak several languages, and multilingual companies have a better competitive edge than monolingual ones.

12 Languages are related to each other like the members of a family. Most European languages belong to the large Indo-European family.

13 Most European languages belong to three broad groups: Germanic, Romance and Slavic.

14 The Germanic family of languages includes Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, Icelandic, German, Dutch, English and Yiddish, among others.

15 The Romance languages include Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian, among others.

16 The Slavic languages include Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Slovenian, Serbian, Croatian, Macedonian, Bulgarian and others.

17 Most European languages use the Latin alphabet. Some Slavic languages use the Cyrillic alphabet. Greek, Armenian, Georgian and Yiddish have their own alphabet.

18 Most countries in Europe have a number of regional or minority languages – some of these have obtained official status.

19 The non-European languages most widely used on European territory are Arabic, Chinese and Hindi, each with its own writing system.

20 Russia (148 million inhabitants) has by far the highest number of languages spoken on its territory: from 130 to 200 depending on the criteria.

21 Due to the influx of migrants and refugees, Europe has become largely multilingual. In London alone some 300 languages are spoken (Arabic, Turkish, Kurdish, Berber, Hindi, Punjabi, etc.).

Source: http://edl.ecml.at/LanguageFun/LanguageFacts/tabid/1859/language/en-GB/Default.aspx

Self-evaluate your language skills

The ‘Self-evaluate your language skills’ game helps you to profile your skills in the languages you know according to the six reference levels described in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) developed by the Council of Europe (Language Policy Unit, Strasbourg). The CEFR exists in 39 languages and is used throughout the world in many contexts.

The game is based on the Self-assessment grid contained in the CEFR and describes language activities.

When answering the questions within the application please remember that this merely aims at setting your language profile and at encouraging you to pursue language learning! The self-assessment full procedure is slightly more demanding!

Play the game:

http://edl.ecml.at/LanguageFun/Selfevaluateyourlanguageskills/tabid/2194/language/en-GB/Default.aspx

Video: