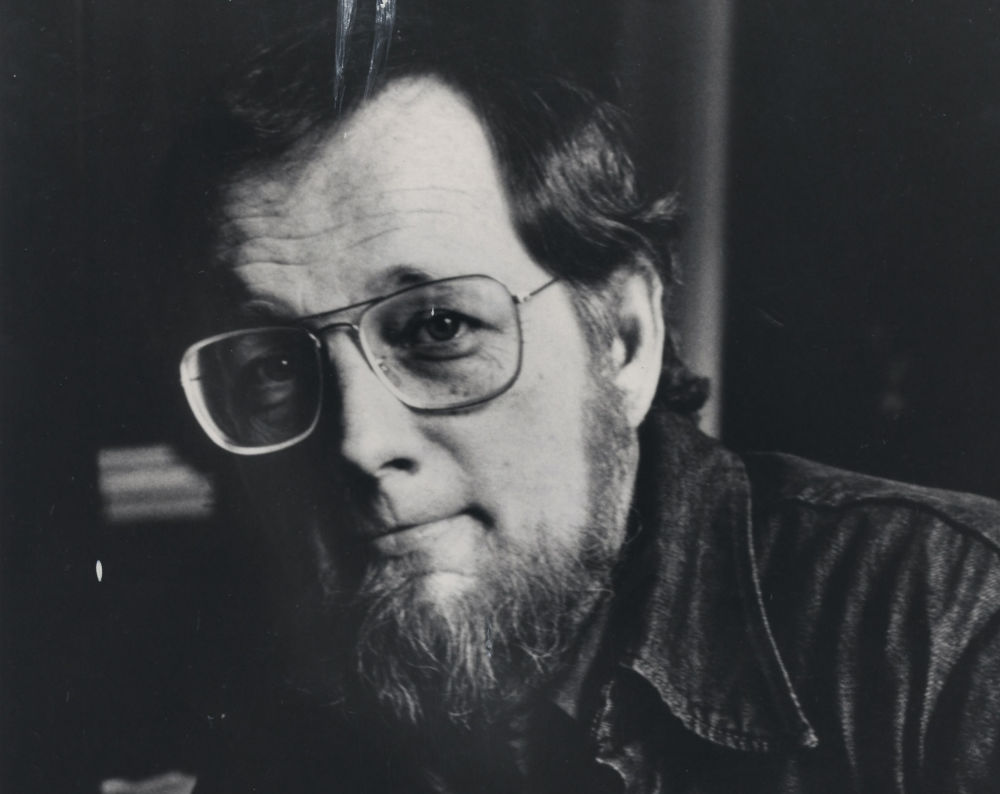

In this video I´d like to invite you to read in English the short story The School by Donald Barthelme and my translation into Spanish. I hope you like it! En este vídeo me gustaría invitaros a leer el relato en inglés La Escuela de Donald Barthelme y mi traducción en español. ¡Espero que os guste!

The School, a short story by Donald Barthelme

La Escuela, un relato de Donald Bartheme

Well, we had all these children out planting trees, see, because we figured that… that was part of their education, to see how, you know, the root systems… and also the sense of responsibility, taking care of things, being individually responsible. You know what I mean. And the trees all died. They were orange trees. I don’t know why they died, they just died. Something wrong with the soil possibly or maybe the stuff we got from the nursery wasn’t the best. We complained about it. So we’ve got thirty kids there, each kid had his or her own little tree to plant and we’ve got these thirty dead trees. All these kids looking at these little brown sticks, it was depressing.

Bueno, teníamos a todos estos niños ahí afuera plantando árboles, ya ves, porque nos imaginábamos que… que era parte de su educación, para ver cómo, ya sabes, el sistema de raíces… y también el sentido de la responsabilidad, al cuidar cosas, al ser responsable de forma individual. Ya sabes lo que quiero decir. Y todos los árboles murieron. Eran naranjos. No sé por qué murieron, simplemente murieron. Posiblemente algo estaba en la tierra o quizá los ejemplares que conseguimos en el vivero no eran los mejores. Nos quejamos por ello. Así que teníamos treinta niños allí, cada niño y cada niña tenía su propio árbol para plantar y obtuvimos estos treinta árboles muertos. Todos estos niños mirando a estos palitos marrones, era deprimente.

It wouldn’t have been so bad except that just a couple of weeks before the thing with the trees, the snakes all died. But I think that the snakes — well, the reason that the snakes kicked off was that… you remember, the boiler was shut off for four days because of the strike, and that was explicable. It was something you could explain to the kids because of the strike. I mean, none of their parents would let them cross the picket line and they knew there was a strike going on and what it meant. So when things got started up again and we found the snakes they weren’t too disturbed.

No habría sido tan malo si no fuera porque justo un par de semanas antes del asunto de los árboles, las serpientes murieron. Pero yo creo que las serpientes –bueno, la razón por la que las serpientes murieran fue que… te acuerdas, la caldera se quedó sin suministro durante cuatro días a causa de la huelga, y eso se podía explicar. Era algo que podías explicar a los chicos causa de la huelga. Es decir, que ninguno de sus padres les dejaría cruzar la línea del piquete y sabían que una huelga se estaba llevando a cabo y lo que aquello significaba.

With the herb gardens it was probably a case of overwatering, and at least now they know not to overwater. The children were very conscientious with the herb gardens and some of them probably… you know, slipped them a little extra water when we weren’t looking. Or maybe… well, I don’t like to think about sabotage, although it did occur to us. I mean, it was something that crossed our minds. We were thinking that way probably because before that the gerbils had died, and the white mice had died, and the salamander… well, now they know not to carry them around in plastic bags.

Con los jardines de hierbas fue probablemente un caso de riego en exceso y algunos de ellos probablemente… ya sabes, les echaban un poco de agua extra cuando no estábamos mirando. O quizá… bueno, no me gusta pensar en sabotaje, aunque nos ocurrió. Quiero decir, que fue algo que se nos pasó por la mente. Probablemente pensábamos así, porque antes de eso, los jerbos habían muerto, y el ratón blanco había muerto, y la salamandra… bueno, ahora saben que no los deben por ahí en bolsas de plástico.

Of course we expected the tropical fish to die, that was no surprise. Those numbers, you look at them crooked and they’re belly-up on the surface. But the lesson plan called for a tropical fish input at that point, there was nothing we could do, it happens every year, you just have to hurry past it.

Desde luego, supusimos que el pez tropical moriría, no fue una sorpresa. Esos números, los miras doblado y están panza arriba en la superficie. Pero el plan de las unidades requería que en aquel momento se introdujera un pez tropical, no había nada que pudiéramos hacer, ocurre cada año, simplemente tienes que pasarlo rápidamente.

We weren’t even supposed to have a puppy.

Incluso no se suponía que tuviéramos un cachorro.

We weren’t even supposed to have one, it was just a puppy the Murdoch girl found under a Gristede’s truck one day and she was afraid the truck would run over it when the driver had finished making his delivery, so she stuck it in her knapsack and brought it to the school with her. So we had this puppy. As soon as I saw the puppy I thought, Oh Christ, I bet it will live for about two weeks and then… And that’s what it did. It wasn’t supposed to be in the classroom at all, there’s some kind of regulation about it, but you can’t tell them they can’t have a puppy when the puppy is already there, right in front of them, running around on the floor and yap yap yapping. They named it Edgar — that is, they named it after me. They had a lot of fun running after it and yelling, “Here, Edgar! Nice Edgar!” Then they’d laugh like hell. They enjoyed the ambiguity. I enjoyed it myself. I don’t mind being kidded. They made a little house for it in the supply closet and all that. I don’t know what it died of. Distemper, I guess. It probably hadn’t had any shots. I got it out of there before the kids got to school. I checked the supply closet each morning, routinely, because I knew what was going to happen. I gave it to the custodian.

Incluso no se esperaba que tuviéramos, simplemente fue un cachorro que la chica de Murdoch un día encontró debajo de un camión de Gristede y tenía miedo de que el camión le pasara por encima, cuando el conductor hubiera acabado de hacer su reparto, así que lo metió en su mochila y lo trajo consigo al colegio. Así que tuvimos este cachorro. Tan pronto como vi el cachorro, pensé, oh Señor, apuesto a que vivirá unas dos semanas, y entonces… Y eso fue lo que hizo. No se suponía que tuviera que estar de ninguna manera en la clase, hay ciertas normas respecto a eso, pero no les puedes decir que no pueden tener un cachorro cuando el cachorro ya está ahí, justo en frente de ellos, corriendo por el suelo ladrando y ladrando. Lo llamaron Edgard –eso es, lo llamaron por mi nombre. Se divertían muchísimo corriendo detrás de él y gritando, “¡Aquí, Edgar! ¡Bien, Edgar!” Entonces se explotaban a la risa. Disfrutaban de la ambigüedad. Yo también la disfruté. No me importa que se bromeen de mí. Le hicieron una casita en el cuarto de la limpieza y todo eso. No sé de qué murió. Moquillo, supongo. Probablemente no había recibido vacuna alguna. Lo saqué de allí antes de que los chicos llegaran al colegio. Comprobaba el cuarto de la limpieza cada mañana, de forma rutinaria, porque sabía lo que iba a ocurrir. Se lo di al guardián.

And then there was this Korean orphan that the class adopted through the Help the Children program, all the kids brought in a quarter a month, that was the idea. It was an unfortunate thing, the kid’s name was Kim and maybe we adopted him too late or something. The cause of death was not stated in the letter we got, they suggested we adopt another child instead and sent us some interesting case histories, but we didn’t have the heart. The class took it pretty hard, they began (I think, nobody ever said anything to me directly) to feel that maybe there was something wrong with the school. But I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the school, particularly, I’ve seen better and I’ve seen worse. It was just a run of bad luck. We had an extraordinary number of parents passing away, for instance. There were I think two heart attacks and two suicides, one drowning, and four killed together in a car accident. One stroke. And we had the usual heavy mortality rate among the grandparents, or maybe it was heavier this year, it seemed so. And finally the tragedy.

Y entonces estuvo este huérfano coreano, que la clase adoptó a través del programa Ayuda a los Niños, todos los niños traían una moneda de veinticinco al mes, esa era la idea. Fue algo desafortunado, el nombre del muchacho era Kim y puede que lo adoptáramos demasiado tarde o algo así. La causa de la muerte no aparecía en la carta que recibimos, sugirieron que adoptáramos otro niño en su lugar, y nos enviaron los historiales de algunos casos interesantes, pero no tuvimos el coraje. La clase se lo tomó muy mal, empezaron (creo, nadie nunca me dijo algo a mí directamente) a pensar que quizá había algo que iba mal en la escuela. Pero yo no creo que haya algo mal en la escuela, particularmente, he visto momentos mejores y he visto momentos peores. Sólo fue una racha de mala suerte. Tuvimos un número extraordinario de padres que fallecieron, por ejemplo. Se produjeron, creo, dos infartos y dos suicidios, un ahogamiento, y cuatro se mataron juntos en un accidente de coche. Un derrame cerebral. Y tuvimos al habitual porcentaje grande de mortalidad entre los abuelos, o quizá fuera mayor este año, parecía así. Y finalmente la tragedia.

The tragedy occurred when Matthew Wein and Tony Mavrogordo were playing over where they’re excavating for the new federal office building. There were all these big wooden beams stacked, you know, at the edge of the excavation. There’s a court case coming out of that, the parents are claiming that the beams were poorly stacked. I don’t know what’s true and what’s not. It’s been a strange year.

La tragedia ocurrió cuando Matthew Wein y Tony Mavrogordo estaban jugando allá por donde están excavando para el nuevo edificio de oficinas federal. Estaban todas estas vigas de madera apiladas, ya sabes, al borde de la excavación. Se va a abrir un proceso judicial de todo eso, los padres sostienen que las vigas estaban malamente apiladas. Yo no sé lo que es verdad y lo que no. Ha sido un año extraño.

I forgot to mention Billy Brandt’s father who was knifed fatally when he grappled with a masked intruder in his home.

Olvidé mencionar al padre de Billy Brandt, que fue acuchillado de muerte cuando forcejeaba con un intruso enmascarado en su casa.

One day, we had a discussion in class. They asked me, where did they go? The trees, the salamander, the tropical fish, Edgar, the poppas and mommas, Matthew and Tony, where did they go? And I said, I don’t know, I don’t know. And they said, who knows? and I said, nobody knows. And they said, is death that which gives meaning to life? And I said no, life is that which gives meaning to life. Then they said, but isn’t death, considered as a fundamental datum, the means by which the taken-for-granted mundanity of the everyday may be transcended in the direction of —

Un día tuvimos una debate en clase. Ellos me preguntaron, ¿a dónde se fueron? Los árboles, la salamandra, el pez tropical, Edgar, los yayos y las yayas, Matthew y Tony, ¿a dónde se fueron? Y yo dije, no sé. No sé. Y dijeron, ¿quién sabe? Y dije, nadie sabe. Y ellos dijeron, ¿es la muerte lo que da significado a la vida? Y yo dije, no, la vida es lo que da significado a la vida. Entonces dijeron, pero no es la muerte, considerada como una fecha fundamental, el medio por el cual la infravalorada mundanal vida cotidiana podría ser trascendida en la dirección de–

I said, yes, maybe.

Yo dije, sí, puede ser.

They said, we don’t like it.

Ellos dijeron, no nos gusta.

I said, that’s sound.

Yo dije, eso parece.

They said, it’s a bloody shame!

Ellos dijeron, ¡es una maldita desgracia!

I said, it is.

Yo dije, lo es.

They said, will you make love now with Helen (our teaching assistant) so that we can see how it is done? We know you like Helen.

Ellos dijeron, ¿harás ahora el amor con Helen (nuestra profesora asistente), para que podamos ver cómo se hace? Sabemos que te gusta Helen.

I do like Helen but I said that I would not.

Sí que me gusta Helen, pero dije que no lo haría.

We’ve heard so much about it, they said, but we’ve never seen it.

Hemos oído tanto sobre ello, dijeron, pero nunca lo hemos visto.

I said I would be fired and that it was never, or almost never, done as a demonstration. Helen looked out of the window.

Dije que me despedirían y que nunca, o casi nunca, se hacía como una demostración. Helen miraba por la ventana.

They said, please, please make love with Helen, we require an assertion of value, we are frightened.

Dijeron, por favor, por favor haz el amor con Helen, exigimos una afirmación de valor, tenemos miedo.

I said that they shouldn’t be frightened (although I am often frightened) and that there was value everywhere. Helen came and embraced me. I kissed her a few times on the brow. We held each other. The children were excited. Then there was a knock on the door, I opened the door, and the new gerbil walked in. The children cheered wildly.

Yo dije que no deberían tener miedo (aunque yo a menudo tengo miedo) y que había valor por todas partes. Helen entró y me abrazó. La besé varias veces en la frente. Nos abrazamos. Los niños estaban entusiasmados. Entonces alguien tocó a la puerta. Abrí la puerta, y el nuevo jerbo entró. Los niños vitorearon como locos.

Fuente: https://electricliterature.com/the-school-donald-barthelme/